The 1805 Club uses cookies to ensure you have the best possible online experience. By continuing to use this site you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our cookie policy.

Historical Articles

A collection of articles and personal research projects by society members

Resistance to the Second Vatican Council -The full version-The Spread of unauthorised Mass Centres in Britain in the 1970s

The Full Version

Resisting the Second Vatican Council: The Story of Lancashire Traditionalist Catholics Derrick and Irene Taylor

Brandon Reece Taylorian

On the evening of 8th October 1975, journalists Darryl Freedman and David Graham tentatively drove their car down the dark and winding driveway of a large house at Longmeanygate on the outskirts of Leyland. As they pulled up to the house, they were greeted by Derrick Taylor, his wife Irene and several of their children, along with a charismatic priest named Peter Morgan. That night, Freedman and Graham witnessed Father Morgan celebrate Latin Mass in the Tridentine Rite in the makeshift chapel Mr and Mrs Taylor had constructed in their kitchen. Several families attended the Mass who shared Mr and Mrs Taylor’s view that the shift to celebrate Mass in the vernacular rather than in Latin that came about after the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) was wrong. The following day, Mr and Mrs Taylor’s house chapel and the comments they made in their interviews were splashed across the front page of the Lancashire Evening Post and they were labelled ‘rebels.’

Derrick Taylor was born on 12th August 1930 in the mining town of Coppull. Despite being Christened in the Church of England, when he was seven years old, Mr Taylor saw for the first time an image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in the hallway of his friend’s house and became enamoured with this representation of Jesus. Almost two decades later and spurred on by another spiritual awakening he experienced while on a pilgrim trail called the Crosses of Knockalla in Northern Ireland in 1949, Mr Taylor satisfied his instinct by deciding to convert to Roman Catholicism, helped along by his fiancée Irene who

was two years his junior and born a descendant of an Irish Catholic family from Preston. After Mr Taylor took lessons from Father Patrick McNally at St Mary’s Church in Bamber Bridge for two years, he converted in 1952, the couple married in 1954 and Mr Taylor completed his conversion with his Confirmation in 1956.

After the death of Mr Taylor’s father in a road accident in January 1954 followed by the tragic death of their first son Derrick Stephen after a home birth in December of that year and following the death of Irene’s father from cancer in 1962, the couple, who by this time already had a growing family of five children, used their inheritance to buy Bannister Farm on Longmeanygate in Midge Hall. Mr Taylor got to work at building what would become the Taylor family’s home for the next fifty years. All was well until the results of the Second Vatican Council were announced, changing or making optional many customs that Mr and Mrs Taylor had been told were integral to the Catholic faith that made it ‘right’ compared to all other Christian denominations, including celebrating the Mass in Latin.

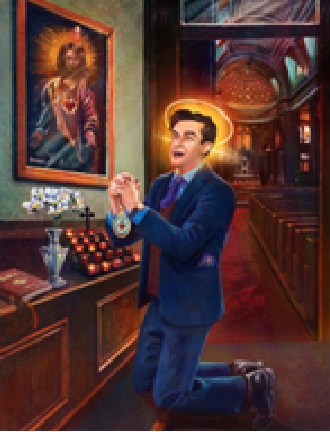

With his faith shaken because of the changes, Mr Taylor entered St Wilfrid’s Church in Preston in a disillusioned state on 31st May 1971. After saying his prayers in the Chapel of the Sacred Heart beside the altar, including asking God for guidance on what he could do to help the Church from taking what he thought was the wrong path, Mr Taylor returned to the narthex at the rear of the church and knelt before a picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus which is still displayed in St Wilfrid’s today. In that moment, Mr Taylor claimed to hear the voice of God utter the words: “Keep up with your Mass. Everything is all right.”

An illustration of The Locution of the Sacred Heart in St Wilfrid’s Church, Preston, in 1971 by David Young, published in 2022.

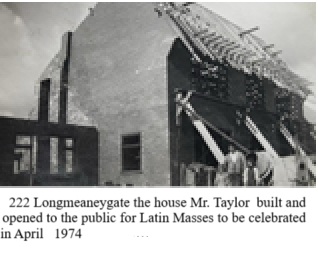

While modernists have since interpreted these words to mean to keep up with the Mass no matter its form, Mr Taylor interpreted his locution to mean to continue attending the Tridentine Rite of the Mass that the Church had abandoned, but this would be no easy task. At the time, it was difficult to find priests who would celebrate the Mass in the Tridentine rite so when in April 1973, Mr and Mrs Taylor met Father Peter Morgan while on a visit to their friends Mr and Mrs Irwin in Somerset, the Taylors were thrilled and quickly joined Morgan’s St Pius V Association.The Taylors began preparing their home so that Mass could be celebrate there and by 1976, their house 222 Longmeanygate became the main Mass centre in the North West of England for the St Pius V Association. The Taylors hosted priests and traditionalist Catholics from across the country and in the summer months, they allowed Association priests to use the field they owned beside their home for large outdoor Masses, one of which was celebrated by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre who was the founder of the Society of St Pius X (SSPX). However, the Taylors did not remain active organisers in the SSPX because by 1978, when Father Morgan stepped down as Superior, the SSPX was looking to established bona fide churches for its Masses rather than private residences, leaving their house chapel redundant. Like many other families who had been early members of Morgan’s Association, the Taylors felt insulted considering all their efforts to build a thriving congregation. Their relations with the SSPX had already weakened when Archbishop Lefebvre was forbidden from exercising his priestly functions in 1976 and who was eventually excommunicated in 1988.

As for Mr and Mrs Taylor, they somewhat retreated from public view, planting trees around their house so that it could not be seen from the roadside and allowed only family members to visit or friends they trusted. After some time as casual supporters of Opus Dei, the Taylors joined the Latin Mass Society which unlike SSPX was in good standing with the Vatican and continued to have their house inside decorated as a pilgrimage site for Catholics, with life-size statues and all manner of Catholic devotions displayed throughout the house, including a stoup of holy water in the entryway. After suffering from ill-health for many years due to heart disease, Mr Taylor died in 2011, followed by Mrs Taylor in 2015, who despite suffering from bowel cancer refused to take any painkillers on her deathbed, saying: “I must suffer for my own sins and for those of humanity.”

If you wish to know more about the life of Irene and Derrick, visit www.irenemary.com. If wish to share your thoughts on my research, I would be happy to hear from you, please contact me at brtaylorian@uclan.ac.uk

Atticus on the Mormons

Atticus on the Mormons

The following article is taken from The Moulding Family History website (The Mormons | Moulding Family History) It is a transcript of an article written in the Preston Chronicle series of 1869, ‘Churches and Chapels, their priests, parsons and congregations’ by the Victorian Journalist Anthony Hewitson (1836–1912), AKA ‘Atticus’, and sent to the Preston Historical Society by member Ben Humphries. If, initially, the reader believes this to be a view of the Mormons shared by Preston Historical Society, they should soon be abused of that belief by the ‘Victorian’ language used in the article. The Society has no particular views on the thrust of the article, but see it as an historical document in which Atticus not only gives us the history of the founding of the Mormon faith, and sheds a light on 19th century working class Prestonian speech patterns, but also demonstrates his cutting wit and propensity to debunk what he sees as religious cant, humbug, and, as he puts it ‘earnest “abysmal nonsense”’.

The following article, then, is one view on the Church of the Latter-Day Saints, but The PHS talk by Martin Cook ‘ The role of Preston in the development of the world-wide Church of the Latter-day Saints’ on 14th October 2024 stimulated a great deal of interest and feedback and, gave us a completely different perspective on the movement in the 21st century. Armed, then, with two such diverse views the reader is invited to make up their own mind.

N.B.

See also a previous Members Article, ‘The Mormon Moons of Lancashire’ by Brandon Reece Taylorian if you want yet another perspective.

The Mormons

Churches and Chapels by Atticus (Contents)

There are about 1,100 different religious creeds in the world, and amongst them all there is not one more energetic, more mysterious, or more wit-shaken than Mormonism. It is a mass of earnest “abysmal nonsense,” an olla-podrida of theological whimsicalities, a saintly jumble of pious staff made up – if we may borrow an idea – of Hebraism, Persian Dualism, Brahminism, Buddhistic apotheosis, heterodox and orthodox Christianity, Mohammedanism, Drusism, Freemasonry, Methodism, Swedenborgianism, Mesmerism, and Spirit-rapping. We might go on in our elucidation; but what we have said will probably be sufficient for present purposes. There are some deep-swimming fish in the “waters of Mormon;” but the piscatorial shoal is sincere enough, though mortally odd-brained and dreamy. On the 22nd of September, 1827, a rough-spun American, named Joseph Smith, belonging to a family reputed to be fond of laziness, drink, and untruthfulness, and suspected of being somewhat disposed to sheep-stealing, had a visit from “the angel of the Lord.” He had previously been told that his sins were forgiven; that he was a “chosen instrument,” &c., and on the day named Joseph found, somewhere in Ontario, a number of gold plates, eight inches long and seven wide, nearly as thick as tin, fastened together by three rings, and bearing inscriptions, in “Reformed Egyptian,” relative to the history of America “from its first settlement by a colony that came from the Tower of Babel at the confusion of tongues, to the beginning of the 5th century of the Christian era.”

These inscriptions were originally got up by a prophet named Mormon were, as before stated, found by Joseph Smith, were read off by him to a man rejoicing in the name of Oliver Cowdery, and they constitute the contents of what is now known as the Book of Mormon. Smith did not translate the “Reformed Egyptian” openly – if he had been asked to do so, he would have said, “not for Joe;” he got behind a blanket in order to do the job, considering that the plates would be defiled if seen by profane eyes; and deciphered them by two odd lapidistic transparencies, called “Urim and Thummin,” which he found at the same time as he met with the records. Report hath it that Joe’s “translation” of the sacred plates is substantially a paraphrase of a romance written by one Solomon Spalding; but the Mormons, or rather the members of “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints,” deny this, and say that at least eleven persons saw the original plates after transcription. They may have seen them; but nobody else has, and Heaven only knows where they are now.

Did you ever, gentle reader, see the “Book of Mormon?” We have one before us, purchased from a real live Salt Lake missionary; but it is so dreadfully dry and intricate, and seems to be such a dodged-up paraphrase of our own Scriptures, that we are afraid it will never do us any good. It professes to be a “record of the people of Nephi, and also of the Lumanites their brethren, and also of the people of Jared, who came from the tower.” The Mormons think it equal in divine authority to, and a positive corollary of, the Old and New Testaments. It consists of several books, and many chapters; the books being those of Nephi, Jacob, Enos, Jarom, Mosiah, Alma, Helaman, Nephi, Mormon, Ether, and Moroni. The language is quaint and simple in syllabic construction; but the book altogether is a mass of dreamy, puzzling history – is either a sacred fiction plagiarised, or a useless and senile jumble of Christian and Red Indian tradition. Smith, the founder of Mormonism, had only a rough time of it. His Church was first organised in 1830, in the State of New York. Afterwards the Mormons went into Ohio, then established themselves in Missouri, were next driven into Clay County, subsequently look refuge in Illinois, and finally planted themselves in the valley of the great Salt Lake, where they may now be found.

Smith came to grief in 1844, by a pistol shot, administered to him in Illinois by a number of roughs; and Brigham Young, a man said to be “very much married,” and who will now be the father of perhaps 150 children, was appointed his successor. Mormonism is disliked by the bulk of people mainly on account of its fondness for wives. The generality of civilised folk think that one fairly matured creature, with a ring on one of her left-hand fingers, is sufficient for a single household – quite sufficient for all the fair purposes of existence, “lecturing” included; but the Latter-day Saints, who were originally monogamists, and whose “Book of Mormon” condemns polygamy, believe in a plurality of housekeepers. They contend that since the finding of the sacred record by Smith there has been a “divine” revelation on the subject, and that their dignity in heaven will be “in proportion to the number of their wives and children” in this.

Leaving the polygamic part of the business, we may observe that the Mormons believe that God was once a man, but is now perfect; that any man may rise into a species of deity if he is good enough; that mortals will not be punished for what Adam did, but for what they have done themselves; that there can be no salvation without repentance, faith, and baptism; that the sacrament – bread and water – must be taken every week; that ministerial action must be preceded by inspiration; that Miraculous gifts have not ceased; that the soul of man “co-existed equal with God;” that the word of God is recorded in all good books; that there will be an actual gathering of Israel, including the Red Indians, whom they regard with much interest as being the descendants of an ancient tribe whose skins were coloured on account of disobedience in some part of America about 2,400 years ago; that the “New Zion” will be established in America; and that there will be a final resurrection of the flesh and bones – without the blood – of men. Some of their moral articles of belief are good, and if carried out, ought to make the Salt Lake Valley a decent, peaceable place, notwithstanding all the wives therein. In one of the said articles they express their belief in being “honest, true, chaste, temperate, benevolent, virtuous, and upright,” and further on they come down with a crash upon idle and lazy persons, by saying that they can be neither Christians nor enjoy salvation.

In 1837, certain elders of the Mormon church, including Orson Hyde and Heber C. Kimball, were sent over to England as missionaries; the first town they commenced operations in, after their arrival, was – Preston; and the first shot they fired in Preston was from the pulpit of a building in Vauxhall-road, now occupied by the Particular Baptists. Things got hot in a few minutes here; it became speedily known that Hyde, Kimball, and Co. were of a sect fond of a multiplicity of wives; and the “missionaries” had to forthwith look out for fresh quarters. They secured the old Cock Pit, drove a great business in it, and at length actually got about 500 “members.” Whilst this movement was going on in the town, the missionaries were pushing Mormonism in some of the surrounding country places. At Longton, nearly everybody went into raptures over the “new doctrine;” Mormonism fairly took the place by storm; it caught up and entranced old and young, married and single, pious and godless; it even spread like a sacred rinderpest amongst the Wesleyans, who at that time were very strong in Longton – captivating leaders, members, and some of the scholars in fine style; and the chapel of this body was so emptied by the Mormon crusade, that it was found expedient to reduce it internally and set apart some of it for school purposes. To this day the village has not entirely recovered the shock which Mormonism gave it 30 years ago. During the heat of the conflict many Longtonians went to the region of Mormondom in America, and several of them soon wished they were back again.

In Preston, too, whilst the Cock Pit fever was raging numbers “went out.” After the work of “conversion,” &c., had been carried on for a period in the sacred Pit mentioned, the Mormons migrated to a building, which had been used as a joiners shop, in Park-road; subsequently they took for their tabernacle an old sizing house in Friargate; then they went to a building in Lawson-street now used as the Weavers’ Institute, and originally occupied by the Ranters; and at a later date they made another move – transferred themselves to a room in the Temperance Hotel, Lime-street, which they continue to occupy, and in which, every Sunday morning and evening, they ideally drink of Mormondom’s salt-water, and clap their hands gleefully over Joe Smith’s impending millenium. There are only about 70 members of the Mormon Church in Preston and the immediate neighbourhood at present; but they are all hopeful, and fancy that beatification is in store for them. We had recently a half-solemn, half-comic desire to see the very latest development of Preston Mormonism in its Lune-street home; but having an idea that strangers might be objected to whilst the “holding forth” was going on, that, in fact, the members had resolved themselves, through diminished numbers, into a species of secret conclave, we were rather puzzled to know how the business of seeing and hearing could be accomplished.

Nevertheless we went to the Temperance Hotel, and after some conversation with a person there – not a Mormon – we decided to go right into the meeting-room, the idea being that, under any circumstances, we could only be pitched into, and then pitched out. And with this notion we entered the place, put our hat upon a table deliberately, took a seat upon a form quietly, and then looked round coolly in anticipation of a round of sauce or a trifle of fighting. But peace was preserved. There were just six living beings in the room – three well-dressed moustached young men, a thinly-fierce-looking woman, a very red-headed youth, and a quiet little girl. For about 30 seconds absolute silence prevailed. The thin woman then looked forward at the red-haired youth and in a clear voice said “Bin round there yet – eh?” which elicited the answer “Yea, and comed whoam.” “Things are flat there as well as here aren’t they – eh?” And the red-haired youth said “Yea.” “Factories arn’t doing much now, are they?” said she next, and the rejoinder was “They arn’t; bin round by Bowton, and its aw alike.”

This slightly refreshing prelude was supplemented by sapient remarks as to the weather &c.; and we were beginning to wonder whether the general service was simply going to amount to this kind of conversation or be pushed on “properly” when in stepped a strong-built dark-complexioned man, who marched forward with the dignity of an elder, until he got to a small table surmounted by a desk, whence he drew a brown paper parcel, which he handed to one of the moustached young men, who undid it cautiously and carefully, “What is it going to be?” said we, mentally; when, lo! there appeared a white table cloth, which was duly spread. The strong built man then dived deeply into one of his coat pockets, and fetched out of it a small paper parcel, flung it upon a form close by, seized a soup plate into which he crumbled a slice of bread, then got a double-handled pewter pot, into which he poured some water, and afterwards sat down as generalissimo of the business. The individual who manipulated with the table cloth afterwards made a prayer, universal in several of its sentiments; but stiffened up tightly with Mormon notions towards the close. Two elderly men and a lad entered the room when the orison was finished, and a discussion followed between the “general” and the young man who had been praying as to some hymn they should sing. “Can’t find the first hymn,” said the young man; and we thought that a pretty smart thing for a beginning. “Oh, never mind – go farther on – any – long meter,” uttered his interlocutor, and he forthwith made a sanguine dash into the centre of the book, and gave out a hymn.

The company got into a “peculiar metre” tune at once, and the singing was about the most comically wretched we ever heard. The lad who came in with the elderly men tried every range of voice in every verse, and thought that he had a right to do just as he liked with the music; the elderly men near him hammed out something in a weak and time-worn key; the woman got into a high strain and flourished considerably at the line ends; the little girl said nothing; the three young men seemed quite unable to get above a monotonous groan, and the general looked forward, then down, and then smiled a little, but uttered never a word, and seemed immensely relieved when the singing was over. The bread which had been broken into the soup plate was next handed round, and it was succeeded by the pewter pot measure of water. This was the sacrament, and it was partaken of by all – the young as well as the old. During the enactment of this part of the programme a gaily-dressed young female, sporting a Paisley shawl, ear-rings, a chignon, a small bonnet, and the other accoutrements of modern fashion, dropped in, and also took the sacrament. Another hymn was here given out, and the young woman with the Paisley shawl, &c., rushed straight into the work of singing without a moment’s warning. She carried the others with her, and enabled them to get through the verses easily. Just when the singing was ended, a rubicund-featured and bosky female, who had, perhaps, seen five-and-forty summers, landed in the room, took a seat, and then took the sacrament. She was the last of the Mohicans, and after her appearance the door was closed, and the latch dropped.

Speaking succeeded, and the talkers got upon their feet in accordance with certain nods and memoes from the chairman. They all eulogised in a joyous strain the glories of Mormonism, but never a syllable was expressed about wives. A young moustached man led the way. He told the meeting that he had long been of a religious turn of mind; that he was a Wesleyan until 17 years of age; that afterwards he found peace in the Smithsonian church; that the only true creed was that of Mormonism; that it didn’t matter what people said in condemnation of such creed; and that he should always stick to it. The thin woman, who seemed to have an awful tongue in her head, was the second speaker. She panegyrised “the church” in a phrensied, fierce-tempered, piping strain, talked rapidly about the “new dispensation,” declared that she had accepted it voluntarily, hadn’t been deceived by any one – we hope she never will be – and that she was happy. Her conclusion was sudden, and she appeared to break off just before reaching an agony-point. The third talker was one of the old men, and he commenced with things from “before the foundations of the world,” and brought them down to the present day. His speech was earnest, florid, and rather argumentative in tone. After stating that he had a pious spell upon him before visiting the room, and that the afflatus was still upon him, he entered into a labyrinthal defence of “the church.” “Mormonism,” he said, “is more purer than any other doctrine that is,” and “this here faith,” he continued, “has to go on and win.” He talked mystically about things being “resurrectioned,” contended that the Solomon Spalding theory had been exploded, and quoting one of the elders, said that Mormonism began in a hamlet and got to a village, from a village to a town, thence to a city, thence to a territory, and that if it got “just another kick it would as sure as fate be kicked into a great and mighty nation.” This “old man eloquent” seemed over head and ears in Mormonism, and almost shook with joy at certain points of his discourse. The fourth, and the last, speaker was the chairman. He raised his brawny frame slowly, held a Bible in one hand, and started in this fashion – “Well I s’pose I’ve to say something; but I can’t tell what it’ll be.” This declaration was followed up by a long, wandering mass of talk, full of repetition and hypothetical theology – a mixture of Judaism, Christianity, and Mormonism, and from the whole he endeavoured to distil this “fact” that both Isaiah and St. John had made certain prophetic statements as to the Book of Mormon and its transcription by Joe Smith.

It did not, however, appear from what he said that either Isaiah or the seer of Patmos had named anything about the blanket trick which had to be adopted by Joe is translating “the Book.” But that was perhaps unnecessary; and we shall not throw a “wet blanket” upon the matter by further alluding to it. When the chairman had done his speech, the doxology was sung, and this was supplemented by benediction, pronounced by a young man who shut his eyes, stretched his hands a quarter of a yard out of his coat sleeves, and in a most inspired and bishoply style, delivered the requisite blessing. Hand-shaking, in which we found it necessary to join, supervened, and then there was a general disappearance. The whole of the speakers at this meeting – which may be taken as a fair sample of the gatherings – were illiterate people, individuals with much zeal and little education; and the manner in which they crucified sentences, and maltreated the general principles of logic and common-sense, was really disheartening. They are very earnest folk; we also believe they are honest; but, after all, they are “gone coons,” beyond the reach of both physic and argument. We knew none of the Mormons who attended the meeting described, and singular to say the proprietor of the establishment wherein they assembled had no knowledge of either their names or places of abode. They pay him his rent regularly, and he deems that enough. All that we really know of the sect is, that their chairman is either a mechanic or a blacksmith somewhere, is plain, muscular, solemn looking, bass-voiced, and dreamy; and that his flock are a small, earnest, and preciously-fashioned parcel of sincere, yet deluded, enthusiasts.

The Mormon Moons of Lancashire

The Mormon and Quaker Moons of Lancashire: Family Stories of Religious Conversion, Migration and Persecution.

Part 2 – Conversion to The Church of The Latterday Saints.

Brandon Reece Taylorian

In Part 1 (see PHS Newsletter – Autumn 2024) we saw how the Moon family of Hollowforth, near Woodplumpton Lancashire were persecuted for joining the Quakers in 1658. Not content with this, however, a later branch of the family decided to break away again and join the Church of the Latterday Saints (aka The Mormons).

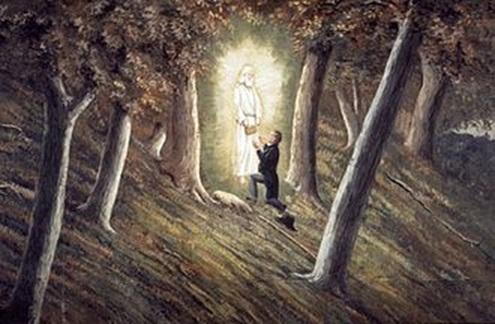

The story of the Mormon Moons mirrors several themes from the Quaker Moons but the most significant fact is that they became the first British Latter-day Saints to migrate to America when they set sail aboard the ‘Britannia‘ at the docks at Liverpool on 6 June 1840. The main branch of the Moons to convert to the new American religion Mormonism were Matthias Moon and his wife Alice. However, a brother and sister named Henry and Hannah Moon, who were distant relatives of Matthias, also converted and joined their relations on the boat to New York. What prompted this radical decision to migrate even before it had become an official policy of the Church was that Matthias died in 1839 and so his wife and children felt their future as Mormons was instead destined for the chosen land of America where they would build a New Jerusalem together alongside their prophet Joseph Smith. Joseph Smith had founded the religion after an angel of God named Moroni appeared to him and said that a collection of ancient writings was buried in a nearby hill in present-day Wayne County, New York, engraved on golden plates by ancient prophets (see Figure 1 below) which inspired him to found the sect.

Figure 1. The Hill Cumorah by C.C.A. Christiansen, Joseph Smith’s vision of Moroni

What is known of the events that took place during this month-and-a-half voyage across the Atlantic Ocean is based on Hugh Moon’s diary entries and a letter that Elder John Moon wrote back to the missionaries in England once the company had arrived in New York and had undergone two days quarantine. In his letter, Moon describes the hellish journey that he and his fellow British Saints had just endured:

“On the 8th was a very high wind and water came over the bulwarks all that day and all sick. I never saw such a day in all my days. Some crying, some vomiting; pots, pans, tins and boxes walking in all directions; the ship heaving the sea roaring and heaved up about 5 or 6 times and was 3 or 4 days as though I was half dead.”

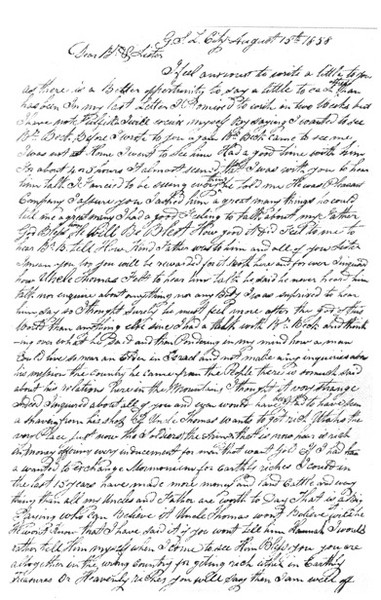

A couple of unforeseen events took place once the company had reached New York. First was that Hannah Moon came into argument with her relative Elder John which prompted her to return to England right away, leaving her brother Henry to carry on without her. The siblings never saw each other in person again but once Henry had settled in Utah ten years later, they began corresponding by letter (see Figure 2). In their correspondence, Hannah focuses on describing the difficult financial conditions she and her husband were facing in England while Henry expressed his sorrow for how his sister had not felt strong enough faith in Prophet Smith to continue with life in America. Henry is persistent in his correspondence to try to convince his sister to come to live in Utah although Hannah never complied.

From New York, the company of Mormon Moons headed westward with the aim of reaching Joseph Smith and other Mormons who had gathered in Nauvoo in Illinois on the border with Iowa by this time. Their overland journey was marred, however, with setbacks caused by low rivers that stalled steamboats, illnesses such as ague affecting many family members and the deaths of some of the older relatives from diseases including bilious fever and cholera. No doubt these circumstances, in addition to the tribulations the company had already faced and the hard labour they had to endure to make ends meet in America, likely prompted some of the Moons to wonder whether they had made the right decision in migrating.

Clear parallels emerge when comparing the close relationship the Quaker Moons had with George Fox and the interactions between the Mormon Moons and Joseph Smith upon reaching Nauvoo. For example, when Henry Moon shook the hand of Joseph Smith, he recorded in his diary how in that moment “he was convinced more than ever that Joseph was the Prophet.” Smith himself presided over an early plural marriage between William Clayton, best known for penning the hymn Come, Come, Ye Saints, and Clayton’s sister-in-law Margaret Moon. Significant was that this marriage took place before Smith’s revelation on 12 July 1843 that sanctioned polygamy and also that Margaret was already betrothed to a man named Aaron Farr, in turn erupting a Mormon melodrama, the emotional details of which Clayton included in his extant diary entries.

Figure 2: Letter from Henry Moon to his sister Hannah Moon back in England 15 August 1858

More than a decade after they had first left Liverpool, Henry Moon recorded in his diary on 5 October 1850 that he and his family finally “reached the Valley of the Great Salt Lake City.” The Moons applied the same entrepreneurial principles in Utah as their ancestors back in Lancashire by setting up businesses,schools and farms to build from scratch a civilisation in the wasteland of the Salt Lake Valley. While Henry Moon himself and most of his offspring were prolific polygamists, by the turn of the twentieth century, polygamy among the Moons had started to wane, although some were stubborn enough as to flee to Mexico to the settlement of Colonia Díaz that the Church had built specifically for polygamists. However, all Moons had returned to Utah by the Mexican Revolution beginning in 1910 which resulted in the destruction of Colonia Díaz in 1912.

The story of the Quaker Moons and Mormon Moons is one of a family whose dedication to new religions in different centuries and setting nonetheless led to similar solemn conversions, persecutions and arduous migrations. In both of the new movements they joined, the Moons grew close with the leader or prophet and were ardent proselytisers, talented writers and hard-working entrepreneurs. In turn, the history of the Moon family’s conversions and migrations not only contribute to the history of the respective religions but to that of Lancashire itself as a hub of religious dissidence.

Edith Rigby

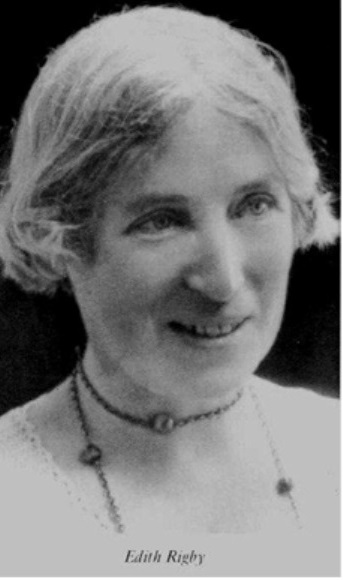

Edith Rigby 1872-1950.

By Peter G Wilkinson.

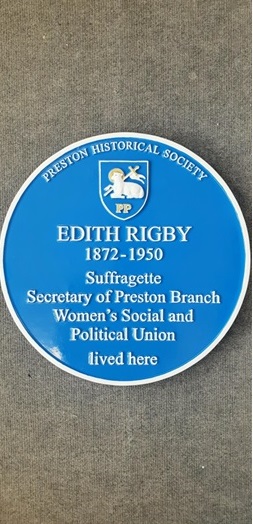

Lots of people will have seen this Blue Plaque on the front of 28 Winckley Square and also been aware of Edith’s suffragette activities whilst she resided here with her husband Dr Charles Rigby.

There follows a brief resumé of her life, provided mainly from Phoebe Hesketh’s book “My Aunt Edith”. Published 1966.

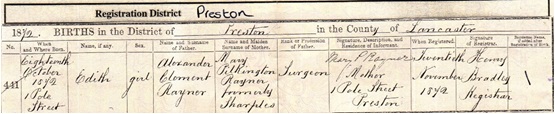

No 1 Pole Street, Preston.

Edith Rigby nee Rayner was born on 18th October 1872 at No 1 Pole Street, Preston. She was the second child of Dr Alexander Clement Rayner and his wife Mary Pikington Rayner, formally Sharples.

She had an older sister Lucy, born 1871 (died 1873) followed by her younger siblings Alice and Arthur (Phoebe Hesketh’s Father). In 1879 they moved into No 58 Pole Street, which was just across the road and slightly higher up. It was here that the rest of the family was born. Herbert, Henrietta and Harold. Situated in the east end of Preston Dr Rayner’s surgery catered for the working and poor classes. Around 1890 when Edith was 18 they moved to Fulwood, but Dr Rayner still kept a surgery at Pole Street.

“Fairview” aka 1 Park Terrace, Fulwood.

The Fulwood house was situated on the corner of Victoria Road and Garstang Road and called “Fairview”. In her book “My Aunt Edith” Phoebe Hesketh tells the story of her wayward brother, Harold , spraying water from a garden syringe, out of the attic window onto the passengers on the top deck of the tram. This would have been a horse draw tram turning into Victoria Road on its way to the Fulwood Barracks terminus. This terrace of houses was originally called Park Terrace and was part of the Fulwood Park Estate, established in the 1850’s.

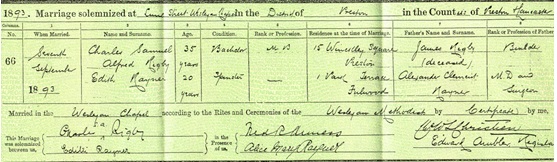

It was from here in 1893 that the 20 year old Edith married Charles S A Rigby.

She was 20 and he was 35!

Dr and Mrs Charles Rigby took up residence at 28 Winckley Square, Preston. Their neighbour was Dr Charles Brown the well respected Preston philanthropist.

It was from this address, over the next twenty odd years that Edith Gained her notoriety. Firstly as a champion for the female factory and mill workers. who were expected to work long hours in very poor conditions, she opened an evening school in St Peter’s School in Brook Street. Secondly as a Suffragette she started the Preston branch of the “Woman’s Social and Political Union” (WSPU) in 1907 and went on to became a thorn in the side of the Establishment!

28 Winckley Square, Preston.

In December 1905 Edith and Charles decided to adopt a two year old boy, who they called Arthur.(after her brother) Arthur, who was known as Sandy, grew up in Winckley Square and attended the local Preston Grammar School in Cross Street.

1913 was a busy year for Edith! There was the incident of the tarring and feathering of Lord Stanley’s statue in Miller Park. Although she claimed responsibility for this , she wasn’t involved with the actual act.

She claimed responsibility for the burning down of Sir William Hesketh’s Property (Royton Lodge) at Rivington and also the planting of a “Bomb” at the Liverpool Cotton Exchange. (This bomb, which caused little damage was more of a giant firework than a bomb.) During this period there was a lot activity surrounding the Suffragette movement and in all Edith was sent to gaol 7 times, many under the “Cat and Mouse” regime!

Her long suffering husband,Charles, had stood by her during this period and written many letters to the government and the local papers. When war broke out in July 1914, the Suffragette suspended all militant activities to concentrate on the war effort.

Edith began looking for a suitable property to grow vegetables and keep bees. She joined the Womans Land Army and started looking for a suitable location. It was at the end of a dusty lane in Penwortham that she found a pair of thatched cottages that were to become their home for the duration and beyond!

This was “Marigold Cottage”

Marigold Cottage.

In 1915 the Rigby Family moved into Marigold Cottage. It was two cottages, an orchard and 5 acres of land at the end of Howick Cross Lane, Penwortham.

Edith immediately set to and painted the cottages, (marigold, what else) cleared the land and prepared the way for bee hives. She organised her friends into collecting and bottling fruit, making jam and generally helping the war effort.

The Women’s Institute (W.I.) was formed in 1915 on Anglesey. The first branch was at Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwlllantysiliogogogoch. (Llanfair PG) The first branch in Lancashire was set up by Edith in 1918 and known as Hutton and Howick Women’s Institute.

It was also around this time she started to follow the teachings and philosophy of Rudolf Steiner. He was the founder of the anthroposophy movement and also advocated eurhythmy. ( spiritual science incorporating movement of the body)

Whilst the Great War was still taking many of our young men away from their jobs back home , the women were stepping in their shoes. The government realised the value of the women’s contribution and on the 6thFebruary 1918 the “Representation of the Peoples Act 1918” passed into law. The act gave women over 30 who were property owners the right to vote! Far from the ideal, but a start. It would take another 10 years to be granted equality!

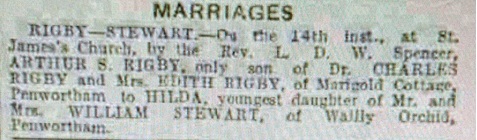

In 1925 Arthur(Sandy) Rigby Married Miss Hilda Stewart at St James’s Church.

By 1926 Edith and Charles were looking around Llandudno for a property to retire to. Edith and her sister Alice had been sent as borders to Penrhos College, North Wales during their teenage years and fallen in love with the area. They finally decided on a property development in the village of Llanrhos , which is just south of Llandudno.

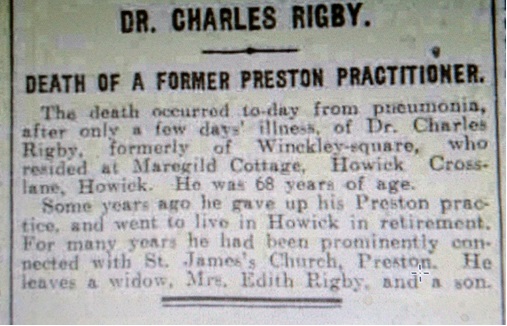

It was here in July 1926, whilst Edith was checking the progress of the house , that she received a message to say that Charles was very poorly. By the time she arrived back at Marigold Cottage , Charles had passed away.

![]()

Erdmut (left) and Mount Grace (right)

Edith Rigby in the later years.

There are few photographs of Edith and little known of her after she left “Marigold Cottage”. In 1926 her husband had died( he was 15 years older than Edith) whilst she was visiting their proposed new home in Llanrhos, North Wales. Her adopted son Arthur (Sandy) had recently got married which left Edith free to follow the teachings of Rudolf Steiner’ He was an Austrian born philosopher, social reformer and follower of esotericism!

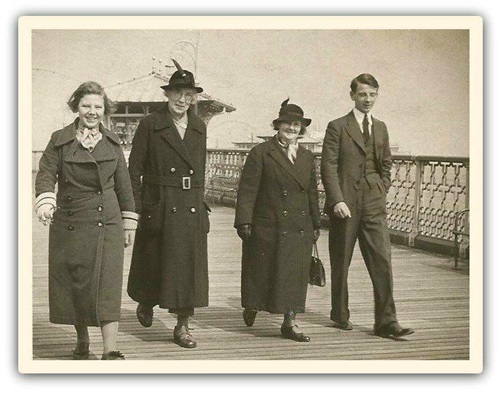

She moved into “Erdmut” St Anne’s Gardens, Llanrhos at the end of 1926, her unmarried younger sister, Alice, moved into the adjoining semi,“Mount Grace”. Here Edith and Alice lived out their days doing all the things the wanted and meeting lots of interesting people. One family that did visit on a regular basis were the Higginson’s. Eleanor Beatrice Higginson was a fellow suffragette and along with her daughter Edith and her son Richard they were captured promenading along Llandudno Pier in 1936. (a rare photograph)

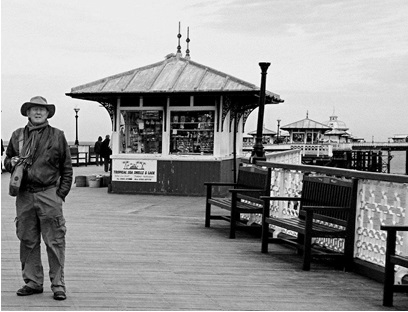

As can be seen from the 2017 photograph below, little has changed!

In later life Edith developed Parkinson,s Disease but it didn’t stop her doing anything, including early morning sea bathing.

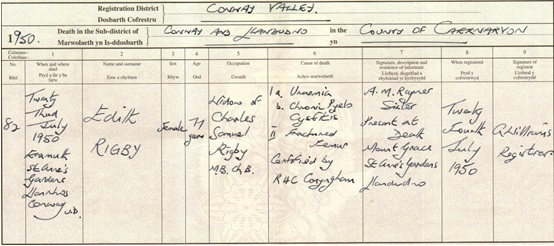

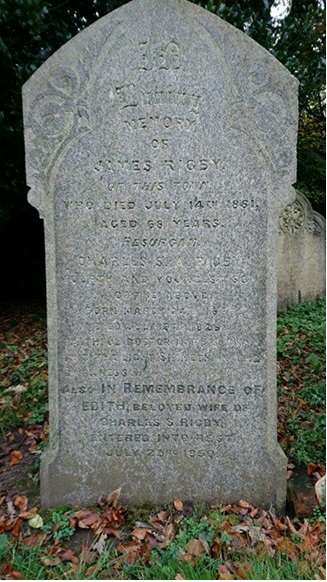

By 1950 she was becoming very frail and had a fall, which resulted in a broken thigh. This and other long standing kidney problems resulted in her death on 23rd July 1950. She died in her own bed with her sister Alice in attendance.

At her own request she was cremated at Birkenhead Crematorium and her ashes were scattered on her husband’s grave in Preston Cemetery.

Preston and slavery

Aidan Turner-Bishop 2020

What was Preston’s involvement in the Transatlantic slave trade? We know that the Lancashire cotton industry flourished greatly on American slave-grown cotton, at least until the abolition of slavery in the USA in 1863 and the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution in 1865. But who owned slaves and invested in plantations? How were local businesses involved? Who profited and what happened to their wealth? What happened to Black people who travelled to north west England? What traces remain?

It’s not easy trying to unravel Preston’s slave trade links in lockdown but plenty has been written if you look carefully. Melinda Elder’s The slave trade and the economic development of 18th century Lancaster (Ryburn, 1992) is useful. There’s also the invaluable online database of compensation paid to slave owners Legacies of British slave-ownership: www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs Lancashire Archives catalogue suggest useful leads. David Hunt’s A history of Preston (Carnegie, 2009, 2nd ed) has some details of Preston’s slave trade.

Firstly, some dates: 1440 the Portuguese begin trading African slaves; 1655 England invaded Jamaica and established slave-based plantations there from the 1670s. The Royal African Company was founded in 1663. Edward Colston (1636–1721) of Bristol – the toppled statue man – was a director. Another leading investor was King James II whose slaves were branded ‘KJ’ (King James). Slavery was abolished in the French colonies in 1793 but restored by Napoleon in 1802. 1807 saw the abolition of the British slave trade; slavery was abolished in the British West Indies in 1834. The Act for the Suppression of the Slave Trade was passed in 1843. The American Civil War (1861–65) led partly to the Lancashire ‘Cotton Famine’ caused by the blockade of Confederate States-suppled cotton. Slavery ended in Brazil in 1888. Many ‘freed’ slaves remained as indentured ‘apprentices’ with little real change in their condition.

In north west England Lancaster (over 29.000 slaves) and Whitehaven (over 14,000) were leading slave ports. The principal centre of the British slave trade was Liverpool: its ships transported over 1,171,171 slaves to America during a trade sometimes euphemistically called the “Guinea” or “Barbados” trade. Liverpool merchants made enormous fortunes, some of which were invested in grand houses such as Speke Hall. For example, Robert Welch, a “Liverpool merchant”, bought High House, Leck, which was converted into Leck Hall, now the seat of the Shuttleworth family.

How did this happen? The business was a ‘trade’, remember. In exchange for slaves, captured and assembled by African chiefs and traders – some Africans became wealthy too – English merchants traded ‘Africa’ (gun) powder, ‘manillas’ (copper bracelet tokens), glass beads, cowrie shells, textiles, cutlasses, iron ingots (some imported from Gammelbo, Sweden), metal goods, and even the skull caps, knitted in Dentdale, Yorkshire, worn by Muslim men. Gingham cloth, woven in Carlisle, and ‘osnaburghs’, slaves’ heavy linen clothing, hand-woven in Leyland and Walton, were also exported. Much ‘Africa’ gun powder was manufactured at Low Wood, Haverthwaite. The work’s records are in Lancashire Archives (DDLO).

Copper was especially important since it was used to make the sugar cane boiling pans and, later, to line the keels of ships to protect them from tropical marine boring worms. Shipbuilding, and its ancillary trades, flourished in Liverpool. Warehouses were needed to store slave goods. Parr’s Warehouse, 26 Colquitt Street, Liverpool, survives today as student accommodation. By its size and solidity you can understand the wealth and importance of the business.

Kirkham merchants built warehouses for the ‘Barbados’ trade at Skippool (1741) and Naze Point, on the Ribble, (1761). In 1754 the Clifton carried local cheeses, shoes, and other goods to Barbados. The Preston sailed to Jamaica. Lloyd’s List in 1755 recorded the voyages of three local ships: the Hothersall (of Poulton) landing 150 slaves in Barbados, the Betty & Martha (Poulton) 65 slaves, and the Blossom (Preston) 131 people. When the Blossom returned to Lytham in 1756 her captain Samuel Gawith offered her sale: “a very strong and tight vessel of proper dimensions and every way compleat for the Slave Trade.” Gawith (or Touchet) continued to trade, making eight further voyages from Liverpool.

Profits from the slave trade were often re-invested as capital in the cotton industry, manufacturing, railways, collieries, land, and country properties, in Britain and across the Empire. An example of this were the Kirkham flax merchants, such as John Birley, who invested with Lancaster slavers in the slave trade at Preston and Poulton. They exported sailcloth and twine needed for the slaving vessels. Merchants like Birley switched to exporting through Liverpool after slave ships ceased sailing from the Ribble and Wyre. Birley later went into partnership with John Swainson to erect in 1828 a huge cotton mill in Fishwick known as ‘The Big Factory’. Fishwick Mill prospered and grew. Birley is recalled today in Birley Street in the city centre.

Fishwick Mill

Who were the local families who organised, financed and profited from the slave trade? The LBS database reveals those who claimed compensation for emancipated slaves. Today we may have an image that slave trading and plantation management was the preserve of brutish men. Certainly, some slave owners were notorious for their sadistic cruelty, sexual abuse, and perverted violence to their slaves. However, for many ‘respectable’ people investment and shares in plantations was good -and legal- business. Ladies, widows, clergymen (such as Rev. William Vernon, Curate of Grindleton), the gentry, aristocracy, tradesmen, and merchants owned shares in slaves. Katie Donington notes that “up until the later stages of the abolition campaign slave-ownership presented no bar to respectability, it was instead a common and unremarked facet of British life” (History Workshop, 2014). You could take out mortgages and loans for slaves. They could be left as legacies in your will. Liverpool’s slaving success may be partly due to the efficiency of its credit arrangements, facilitated by bankers and lawyers who indirectly profited from the trade. Building, equipping, and stocking slave vessels needed finance. Local families saw an opportunity for profitable investment.

Probably the Preston family most deeply involved were the Athertons of Greenbank. Their estate, including the house was sold in 1850 for development (Preston Chronicle, 5 Oct, 1850). It was the land north of Fylde Road. ‘Greenbank’ mansion stood near the site of the UCLan car park in Greenbank Street, formerly Goss’s printing machinery works. Richard Atherton (1738–1804), a ‘draper and woollen merchant’, inherited the Green Park Estate in Jamaica. He was Guild Mayor in 1782, celebrated in doggerel by Mr Wilson: “Joy sparkled and smiled in the face of the Mayor / As he marched through the streets with a right worshipful air”. He is said to have donated some silverware to Preston Corporation’s civic plate collection. He was one of the partners of the Old Bank founded in 1776. This was originally called Atherton, Greaves, and Denison. It stood on the site of the former Trustee Savings Bank, Church Street. He was buried, age 66, on 2 September 1804, in the Minster churchyard. He left the income from his Jamaican estates to his wife Mary. On her death his estates went to his son William, with some payments to his children Lucy, Mary, Edward, Elizabeth and Catherine. Lucy married Sir James Allan Park, a lawyer and judge.

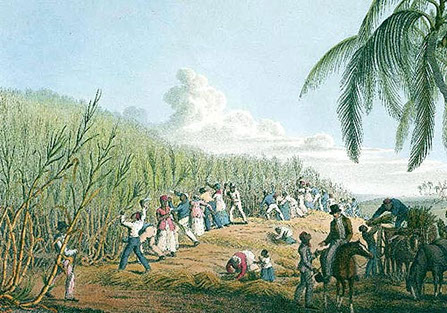

Green Park Sugar Estate was expanded in the 1770s by William Atherton (died 1803) Richard’s brother. He built the plantation house between 1768 and 1769. He added the adjoining Bradshaw Estate in 1771, increasing the estate’s size to 1,315 acres (532 ha). He imported hundreds of African slaves who worked in the cane fields and sugar factories of what was the third largest estate in Trelawney Parish. As a result William became one of the wealthiest planters in Jamaica with an immense fortune which enabled him to buy Prescot Hall, Lancashire, to where he retired. In 1810 the estate had 550 slaves and 302 head of cattle. The Athertons continued to own the estate until 1910 when they sold it to Walter Woolliscroft, the estate manager. The 1929 Crash forced Mr Woolliscroft into bankruptcy as the price of sugar plummeted. Eventually the estate and sugar works closed in 1957; they are now ruins.

Slaves in a sugar plantation, Jamaica.

The wealth did not vanish. It passed among the Atherton family. Dame Lucy, the wife of Judge Sir James Park (1763–1838) was wealthy. At one time the Parks owned a Dutch Old Master painting A cottage in the woods by Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709). It is now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio. Some of the money, including Slave Commission compensation, descended to Eleanora Atherton (1782–1870) who lived in Kersal Cell, near Salford, and 23 Quay Street, Manchester. When Eleanora died in 1870 she left ‘under £400,000’ which, in today’s values, is worth over £25 million. She was known in Manchester for her charitable donations to Chetham’s School, Holy Trinity church, Hulme, and the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge. For the record she received £3,466 8s 8d for Spring Vale Estate slaves and a whopping £10,172 17s 9d for Green Park slaves. Thus was wealth from slavery laundered and made respectable.

Miss Atherton in old age.

Another Preston compensation beneficiary was 27 year old Alexander Hamilton Cameron of 1 Market Place, Preston, where he lived with his wife Elizabeth, a servant, and an apprentice. For his 41 slaves on the Mango Valley Estate he was awarded £693 6s 9d (about £40,143 today). One record that intrigues is an award paid to the Rev R E Harris, ‘rector’ who received £19 10s 10d on 25 January, 1836, for one slave on the

Trelawney Estate (Parliamentary Papers 1836, page 77). Can this be Preston’s celebrated Rector of St George’s, the Rev Robert Harris (1764–1862)? More research may be needed.

The Athertons enjoyed an agreeable lifestyle at Greenbank. The house was set back from Fylde Road: “a neat residence, surrounded with gardens and shrubberies . . . laid out in a tasteful manner.” Tunnicliff (1781) described it as “nearly enveloped amid the foliage of trees”. Greenbank was built before John Horrocks built his Spittal Moss factory nearby. You can get an idea of the Athertons’ wealth and style in their portrait by Arthur Devis (1712–1787) “Mr William Atherton and Mrs Atherton” which now hangs in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. William (1703–1745) was Richard’s son. With great skill the artist painted Mrs Atherton’s very fine and expensive-looking gown. Where did the money come from for the dress?

Mr & Mrs Atherton (Arthur Devis, c 1743)

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

A nice gown: where did the money come from?

Close examination of the LBS database reveals the immense wealth of some Liverpool slave owners such as the Earles, Parkers, Tinnes, and the Gladstones. The Stanley family – the Earls of Derby, who owned Patten House in Preston, were rulers of the Isle of Man: the ‘Lords of Man’. The Isle of Man was deeply involved in the ‘Guinea Trade’ because it acted as a ‘free port’ for slave goods, avoiding Liverpool customs duties. When the 10th Earl of Derby, James II, died in 1736 the Lordship passed to James III, the 2nd Duke of Atholl. After his death in 1764 the British Government proclaimed the 1765 Revesting Act by which the Isle of Man became the property of the British Crown, thereby plugging a slave trade tax loophole. Manx sea captains were active in the trade. The last legal slaving ship from Liverpool in 1807 was Kitty’s Amelia captained by Hugh Crow, a Manxman. But what share of the slave trade profits went to the Earls of Derby?

Cargo lists for Manx ships show the wide variety of slave goods exported to Africa: red carnelian beads (semi-precious gemstone) from India, cotton ‘baft’ and chintz from India, fine linen from Silesia, cowrie shells from the Maldives (used as currency), knives made in England and dried ling fish. The slave trade was a truly international business.

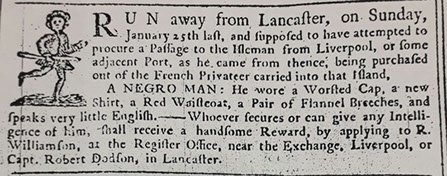

Africans travelled from the West Indies and America to Britain. They came as servants – slaves, indeed – and workmen, maids, cooks and skilled tradesmen. Some fled from their masters who advertised for their return. Some ‘runaway’ advertisements are listed at www.runaways.gla.ac.uk/introduction

Some married, had children and died (remember poor Sambo in his grave at Sunderland Point); many are listed in church registers. For example, one interesting beneficiary of William Atheron’s will was Mary Southworth of Preston. She was a ‘mulatto’ (mixed race) woman who was granted an annuity of £20 (worth £855 today). She was related to Thomas Southworth of Green Park, Jamaica, from whom the Athertons inherited their estates. She may be one of the earliest records of a named Black Preston woman. What happened to her? One difficulty about identifying Black people in old documents is that they used English-sounding surnames. Their ethnicity may be obscured. Some of the church registers of Whitehaven, Cumbria, refer to ‘negro’, ‘mulatto’ or ‘negress’ in their records. What would an investigation of Lancashire records reveal?

The catalogue of Lancashire Archives does refer to records about the slave trade. A user’s guide to these records would be useful. William Atherton’s papers are deposited. Correspondence is held such as a letter from James Irving, a Liverpool mariner, to his wife Mary, dated 2 Dec 1786 (DDX 1126/1/6). He complains of his “very disagreeable cargo” of slaves. He was weary of “this accursed trade”. A revealing, and rather shocking, 12 page lease (DP 513/1) of a plantation in Antigua was made between Justinian Casamajor of Shenley, Hertford, and John Joseph James Vernon of Preston.

The Vernon name is significant. Robert Vernon Atherton Gwillym (c1741–1783) was MP from 1774 to 1780. He married Elizabeth Atherton and inherited Atherton Hall, Leigh. His daughter Henrietta married Thomas Powys, 2nd Baron Lilford in 1797. They were related to the Leghs of Lyme Hall, Cheshire. Incidentally, the Lilford family owned Bank Hall, Tarleton. A pair of lion statues from Atherton Hall, that stood by the front porch of Bank Hall, were moved to the Lilford Estate offices in Tarleton. In 1719 Henrietta Maria Legh donated land on which St Mary’s Church, Tarleton, was built.

The Antigua estate lease in Lancashire Archives names some of the slaves sold to John Vernon. Included in the sale are “Negro Men – Carpenters, Coopers, Masons, Boilers, Carters and Field, Negro Women, Women superannuated (no value), Boys and girls fit and not fit for work and male and female infants “sucking”. The lease deals with the replacement of “distempered” slaves of “low value” who might die and could not be replaced promptly. What happened to John Vernon’s slavery profits? Were they invested in the cotton industry?

Reinvestment in cotton manufacturing was very likely. Eric Williams’s Capitalism and slavery (Andre Deutsch, 1964) makes the telling point that the immense profits from slavery helped to finance banks, industries (such as cotton manufacturing), large estates and what he called the “New Industrial Order”: railways, collieries, factories. Abolition – keenly advocated by some in Lancashire – redirected the wealth but the money had already been made and reinvested. Besides, Lancashire relied on slave-produced cotton from the American Southern States. Colin Dickinson noted that in 1860 over three quarters of Lancashire cotton arrived from the southern slave states. This came to an abrupt hiatus with the American Civil War and the Lancashire ‘Cotton famine’. During the 1860–65 “panic” about half the population of Preston might have been technically paupers such was the disruption of trade. David Hunt points out that the “Famine” was a commercial crisis arising from excessive overproduction in the 1860s boom. This partly prompted speculation about shortages of cotton from the Confederate States. The American Civil War was closely followed in Preston, including news about the Preston-built Confederate naval blockade runner Night Hawk, launched on the Ribble in 1863. Monuments of the Cotton Famine remain today as Avenham and Miller Parks laid out as work creation schemes. It may be no exaggeration to suggest that much of Preston’s cotton industry wealth, at least until the 1860s, depended on slave-produced raw material.

It’s a huge topic worthy of detailed and thorough research; this is just a lockdown glimpse. Many families benefited from the slave trade and compensation awards paid to slave owners. If your family history mentions a “Liverpool merchant”, “Manx captain”, or relatives in the West Indies look closely. Consider Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights in which Mr Earnshaw visits Liverpool ‘on business’ and returns to Yorkshire with the young Heathcliff: a “dark skinned gypsy”, “a little lascar”. There are clues in many unexpected places for rich and often disturbing research topics.

Notes on terminology and sources

Words such as ‘mulatto’, ‘negress’ and ‘negro’ are unacceptable today. However historians have to use them when researching contemporary documents of the period. British pre-decimal currency was based on pounds (£), shillings (s) and pence (d). There were 20 shillings in a pound; 12 pence in a shilling. 17s 6d = 87.5p.

There is a large and expanding bibliography of books, articles, theses, and web resources about the Transatlantic slave trade. A web search will reveal many sources. Brief and useful bibliographies are in Evans (2010) and Sadler (2009). Elder (1992) and Hall (2014) have excellent longer bibliographies. Some sources consulted for this essay include:

Abram W A (1882) Memorials of the Preston Guild (Toulmin)

Atherton Hall https://engole.info/atherton-hall

Belchem, J ed (2006) Liverpool 800 (Liverpool U.P.)

Dickinson, C (2002) Cotton mills of Preston (Carnegie)

Donington, K (2014) The legacies of British slave-ownership (History Workshop)

www.historyworkshop.org.uk/the-legacies-of-british-slave-ownership

Elder, M (1992) The slave trade and the economic development of 18th century Lancaster (Ryburn)

Evans, C (2010) Slave Wales (University of Wales Press). Lucid and informative.

Fowler, C (2020) [National Trust: slavery and colonialism report]

www.nationaltrust.org/mag/colonial-history

Hall, C and others (2014) Legacies of British slave-ownership (Cambridge U P). Bibliography.

Hunt, D (2009) A history of Preston (Carnegie, 2nd ed)

Legacies of British slave-ownership www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs

Manx National Heritage (2007) The Isle of Man and the Transatlantic slave trade. Select bibliography No 14. Available as an online .pdf document.

Mosley, M W (2015) Green Park Sugar Estate: the history

https://thelastgreathouseblog.wordpress.com

Moxon, F S (c1930) A brief history of Pedder & Co, Preston Old Bank, 1776–1861

Osborne, A & Martin, S I (2003?) The slave trade and abolition: sites of memory (English Heritage)

Richardson, D, Schwartz, S & Tibbles, A eds (2007) Liverpool and transatlantic slavery

(Liverpool U P). Melinda Elder’s chapter on The Liverpool slave trade, Lancaster and its environs (pp. 118–137) is especially useful.

Runaway slaves in Britain www.runaways.gla.ac.uk

Sadler, N (2009) The slave trade (Shire). Concise and well-illustrated.

Bibliography.

Taylor, M (2020) The Interest: how the British establishment resisted the abolition of slavery (Bodley Head)

Tunnicliff, W (1781) A topographical survey of the counties of Chester and Lancaster (Nantwich)

Williams, E (1964) Capitalism and slavery (Deutsch)

This essay has not dealt with the Abolition movement in Lancashire or with British military and naval sources used to control plantation and slave revolts in the West Indies: more areas of possible local history research. ATB 2020

‘Ancient Charley’: Artist and Oddfellow

Julie Foster

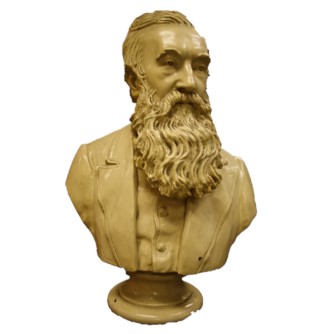

Charles Hardwick (1817–1889) the Preston born ‘antiquarian, historian, archaeologist, artist, art-critic, odd-fellow and good-fellow both’, the author of A History of Preston and its Environs (1857), had early artistic ambitions.

Image courtesy of the Harris Museum, Art Gallery & Library

The son of a ‘respectable publican’ (William Hardwick, landlord of the Grey Horse, Fishergate) Hardwick was first apprenticed at 14 to the Preston Chronicle newspaper. He was awarded first prize for a drawing in chalk from the lesser, and perfectly nude ‘Towneley Venus’ (British Museum) by the fledgling Preston Society of Arts and he was ‘seized by an ambition to become an artist’. The Society elected Hardwick as a member in 1834. It held exhibitions in ‘two large rooms attached to the Court House’ in Preston. Hardwick had attended a ‘private drawing class’ in Preston, alongside his colleague from the Chronicle Jeremiah Thornley (d.1904), who recalled that Hardwick possessed ‘skill enough to have ranked at the top of his profession had he so willed it’. Hardwick ‘painted several noted works in oil’ including a painting of Hamlet and the Ghost later purchased by Thornley, and Macbeth and his guilty wife but he conceded that the ‘technique was somewhat crude and immature’ mentioning two oil studies King Lear and Macbeth suffering the paint ‘peeling off’ after being stored in poor conditions. Hardwick was said by Thornley to be something of a Hamlet obsessive, spending his days brooding over Shakespeare, ‘haunted and in touch with the metaphysical melancholy character of Hamlet’. His wife Elizabeth, a dressmaker, was ‘prevailed upon to make him a doublet and cloak’ for the Fancy Dress Ball held during the Preston Guild in 1842. He took part in a performance of Shakespeare speeches at the Theatre Royal Preston in 1847 (in aid of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust at Stratford) attended by the Mayor Thomas Birchall.

Thornley also mentions a life size portrait of himself painted by Hardwick. Thornley later removed to The Bushell Hospital in Goosnargh. An advertised sale of the contents of his home in Avenham Street (where Hardwick also lived for a time) lists the Hamlet and the Ghost painting, but where is his large portrait? It was still in Thornley’s possession at the time of his article.

Heading to London c.1839, age 22, after his father’s death, Hardwick kept a diary of his visit, passing notes of his journal to his ‘friend and fellow student’ Thomas Casson, who would share them with members of the ‘dissolved art class’ back in Preston. Postage was expensive then: ‘a letter to Preston cost eleven pence’. Excerpts were later published in the Papers of the Manchester Literary Club, (of which Hardwick was a founder member, with Benjamin Brierley, Ben Waugh and others, upon moving to Manchester in 1858) and the Manchester Quarterly as Leaves From A London Journal, 1839 (1888) reviewed by the Lancashire Evening Post as ‘written in a chatty style’. Hardwick visits, with a letter of introduction from a mutual acquaintance the former Preston MP John Wood,) the ‘Painter-to-the-Queen’ George Hayter, who, upon hearing that he hailed from Preston, professed ignorance of the town but after mention of Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt and his defeat of the Hon. E.G. Stanley, a friend, he replied, “Yes, yes, I remember it well. The blacking manufacturer was preferred by the Preston electors to the son and heir of Lord Derby!”

Hayter encouraged the young artist and recommended he attend the recently established School of Design, in Cavendish Square. The proprietors were Angel De Villa Lobos, a Drawing Master from the Madrid Academy of Fine Arts, and Scottish sculptor (and friend of Charles Dickens) Angus Fletcher. Hayter advised Hardwick on gaining admission to the Dulwich Gallery and Hampton Court. Hardwick recounts taking a coach to the latter to swoon before the ‘Raffaelles’ and describes an encounter with the Duke of Wellington at the House of Lords. The journal recalls a trip to Italy and the difficulties of studying the ‘neck-breaker’ ceilings of Michael Angelo in the Vatican Sistine Chapel, Hardwick described how he ‘threw myself on my back’ as recommended by the artist Henry Fuseli ‘that irritating little Keeper of the British Royal Academy in London’.

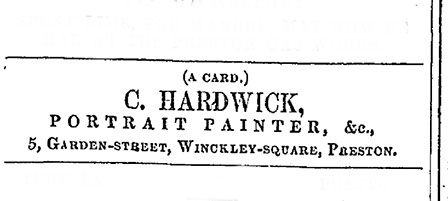

On his return from London Hardwick married Elizabeth Addison, daughter of Thomas Addison, Land Surveyor, of Leyland, at St John’s Church Preston. A daughter, Catherine was born in 1841. The census of that year lists the family (living with, or visiting, Thomas Addison) at the top end of Worden Lane and Towngate, Leyland, then known as Main Street. Hardwick’s profession is listed as Portrait Painter; the Preston Chronicle carried advertisements stating as such.

Elizabeth died in 1842 and is buried in St Andrew’s Church Leyland, which has no Hardwick grave listed. There is an Addison family grave with a later added stone, sadly now illegible, noted as such in the churchyard plan compiled in 1920s.

Hardwick visited London again in 1846, sharing the studio of his friend the Nottinghamshire artist Frederick Charles Cooper, who would later accompany Sir Henry Layard on his excavations of Nineveh.

Hardwick moved with his young daughter to Manchester, in 1858, eschewing art for journalism, having published his History of Preston, writing for such newspapers as the Manchester Examiner and Times and the Salford Weekly News, reviewing art exhibitions in the city and beyond. The articles are preserved in two large scrapbooks entitled Charles Hardwick ‘s contributions to the Press 1866–84 presented to Manchester Central Library by Catherine Hardwick, who perhaps diligently compiled them, carefully clipping out the cuttings. She is described in the Manchester Guardian obituary as ‘his constant companion and helper’.

Before he left Preston, Hardwick was presented with a complete set of the Penny Cyclopaedia, housed in a ‘handsome mahogany carved bookcase, bearing an engraved silver plate’ by members of the Preston Oddfellows, at the Hoop and Crown Inn. In the 1861 Census, he is living at City Road Hulme, age 43, his profession ‘Author and Portrait Painter’. Catherine (21) is a visitor at her maternal Grandfather Thomas Addison’s (age 78) house in Brindle. Other occupants include her Aunt Jane Addison (41) a ‘Professor of Music’.

Hardwick developed his interest in the Oddfellows movement travelling the country delivering lectures, writing articles and pamphlets, editing the Oddfellows Magazine, the short lived journal Country Words, becoming a Grand Master, and writing on subjects such as folklore and archaeology. There are reports of him delivering lectures ‘in his usual argumentative, lucid and eloquent manner’ in an hour and a half. He gave his lecture on the History of Friendly Societies at the Institute for the Diffusion of Knowledge, Preston in 1851. He declaimed the Oddfellows poem written ‘especially for his public recitation’ by his friend and writer Eliza Cook (the handwritten original is in the scrapbook) at the Procession of Friendly Societies at the Preston Guild celebrations. The ‘oldest Oddfellow’ George Ward was celebrated and given a portrait painted by Hardwick at a Preston Lodge gathering.

Hardwick’s art reviews are lengthy, discussing the Manchester Art Treasures exhibition of 1857 ‘pictures too numerous for the available space’ plus the Royal Manchester Institution, Manchester Academy of Fine Art and Royal Academy Summer exhibitions. There are also cuttings of his correspondence. In one letter he recalls being taught drawing ‘fifty years ago’ in Preston by the ‘much respected’ artist Robert Carlyle (1801–1874) whose father Robert Snr. produced many watercolours of Carlisle, held at Carlisle Library. Carlyle Jnr. lived for a time at Springbank, off Fishergate Hill. Hardwick also remembered Robert’s brother, Richard, an artist of ‘miniatures painted on a marble ground’. An advertisement in the Chronicle of Sept 1839 announces Richard Carlyle’s visit to Preston in the coming days, and ‘invites attention to his specimens on ivory and marble, exhibiting at Mr Carr’s Repository, Fishergate and Mr Clarke’s Booksellers, Church Street’.

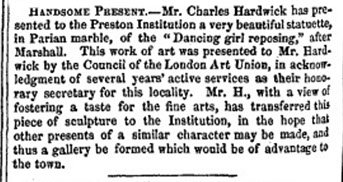

There are favourable reviews of a young Manx artist Joseph Swynnerton ‘a talented young sculptor’ who would later sculpt a plaster bust of Hardwick for the Manchester Literary Club. It was described in the Manchester Evening News: ‘we see the earnestness and keen insight of the face which Time, by manifold buffetings, has vainly striven to deprive of its kindly aspect’. A plaster bust, possibly by Swynnerton, was presented to the new Harris Museum by the Society of Oddfellows. It is currently in store owing to its fragile condition. Hardwick himself had transferred a ‘very beautiful statuette in Parian marble’ (unglazed porcelain) of a Dancing Girl Reposing after William Calder Marshall to the Preston Institution ‘in the hope that other presents of a similar nature would encourage a gallery to be formed in the town’. This had been presented to him by the London Art Union, established in 1836, an organisation which distributed works of art amongst its subscribers by lottery. Hardwick was an Honorary Local Secretary.

Hardwick appears in the Censuses of 1871, 1881 at addresses in Hulme, as ‘Editor of Oddfellows Magazine’, his daughter Catherine’s occupation ‘Housekeeper’. An exhibition of 50 portraits by the artist William Percy at the Manchester Literary Club lists Hardwick as one of the subjects on display.

Oddfellows arms

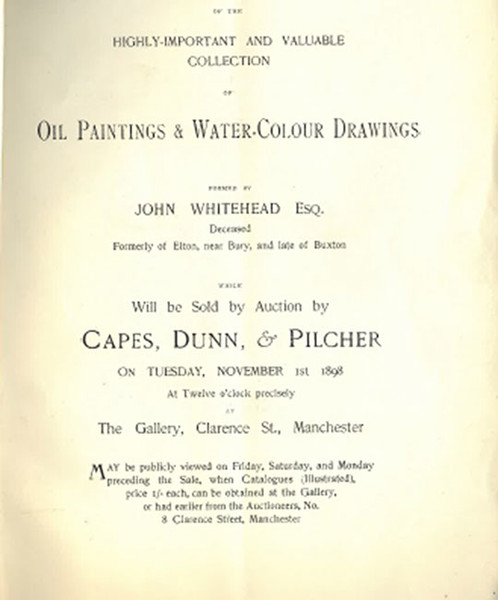

Hardwick’s declining health was reported in the press. He died in 1889, at Talbot Street, Hulme, leaving in his will £1,000. In September 1890, the auctioneers Capes Dunn and Pilcher held a two day sale of books ‘from the library of Mr Charles Hardwick’. An article in the Preston Herald of 1896 reports a presentation of ‘a very handsome marble bust . . . one of four taken of the late Mr Charles Hardwick’ to the Oddfellows Loyal Travellers Rest Lodge, of the Preston district, who met at the British Workmen’s Cafe, Pole Street.

Catherine Hardwick appears on the 1891 census, age 53, having removed to Southport and later Birkdale, described as ‘living on her own means’. An inquest into her death in May 1895 reported in the Liverpool Echo concluded the cause of death was ‘excessive drinking’. She is described as ‘a lady of independent means and well-connected, but had given way to intemperate habits’. She is buried alongside her father at Brooklands cemetery in Sale.

She left effects to the amount of £2,850 in her will, (the equivalent today of £200,000) to a Rev John James Thornley, possibly her cousin. Charles’s sister Elizabeth married John Thornley, a ‘Tea-Dealer’ in 1838, the brother of Jeremiah. In the 1891 Census the Rev. John James Thornley son of John, age 48, b. Preston, is living in Workington, Cumberland, as the Vicar of St John’s Church, with his wife Margaret, and son John Hardwick Thornley age 13. In the 1901 Census the Rev John James Thornley is Vicar of St Oswalds, Kirkoswald, near Penrith. In the 1911 Census the Reverend’s son John Hardwick Thornley age 33 is a Medical Practitioner in Scarborough. His eldest son was Colin Hardwick Thornley (1907–1983) who later became Sir Colin Hardwick Thornley, a colonial administrator and the Governor of British Honduras [now Belize], 1956–1961.

A letter from Catherine Hardwick’s solicitor to Preston Borough Council reported in the Herald details a ‘duty free bequest of picture relievos (bas relief) medallions and a cast, connected with or referring to Thomas Hood’s grave , a portrait of Sir John Hay, and her oil painting representing the subject of The Destruction of the Scarlet Woman’. The Council asked the advice of the Harris Museum Curator and Art Director, Mr W B Barton, formally an art instructor at the Harris Institute, who gave his opinion they were ‘not worthy of being placed in the Free Library and Museum’ and the offer was declined.

Sources

Lancashire Libraries, Lancashire Record Office, South Ribble Museum, Manchester Central Library Archives+, Harris Museum

Some Winckley Square women

By Agnes Stone-Roberts

Winckley Square may be seen as the symbol of the expanding upper middle class in Preston. Two hundred years ago the area in and around the Square housed some of Preston’s leading families but, however picturesque the gardens were, the people in it were no more progressive than in any other area in England with their treatment of women. The education of women was very different from men’s: for starters, many women did not get much schooling.

Portrait of Caroline Norton by Frank Stone.

The formal education of the ‘polite lady’ was generally little more than music, literature, dancing, drawing and needlework. As the early Lancashire historian Peter Whittle said, they regarded ‘. . . all public and private schools as nurseries for men for the service of the church or state, and those for the softer sex as nurseries for piety and virtue’. So not only did the women’s fathers (who in effect owned them) not give them an education that would enable them to survive on their own, when they got married, the bride and all her possessions were regarded as property of their husband. If a woman was unhappy in her marriage the only pathways tended to be: put up with it, or prepare to die a social death.

‘I have learned the law respecting women, piece-meal, by suffering every one of its defects of protection’ – this is what Mrs Caroline Norton, a novelist, poet and mother of three from London wrote to Queen Victoria after her husband treated her cruelly, publicly tried her for adultery, unjustly ruined her reputation, took her father’s legacy, and deprived her of access to her three children; and despite all of this she was not allowed

Engraving of Caroline Norton.

to obtain a divorce. Caroline used her skills and connections to fight back and her passionate campaigning contributed to the passing of the Custody of Infants Act of 1839, the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857, and the Married Women’s Property Act of 1870. These laws, however, were too late or insufficient for many local women whose footsteps through Winckley Square I walk almost every day.

Henrietta ‘Minnie’ Miller (1852–1926) of 5 Winckley Square was the eldest daughter of Thomas Miller the major share–holder of Horrocks’s. Aged 20, she married Sutherland Dumbreck. Everything she previously owned, including the £30,000 (about £3.5m today) she inherited after her father’s death in 1865, belonged to him. They had three children together but from the outset she was physically, verbally and emotionally abused, threatened and cheated on by her husband. The marriage lasted nine years until, though unusual, highly expensive and regarded as social suicide, she filed for a divorce, embracing the Matrimonial Causes Act of

Henrietta Miller

1857, advocated for by Caroline Norton. Though this act was a start, it was by no means easy for women as they needed to prove adultery as well as another offence such as incest, cruelty, bigamy or desertion (a man, on the other hand, only needed to prove adultery to petition divorce). She listed adultery and cruelty – an action that took courage, family support and a respected and wealthy position in that period. Her divorce was heard and the final decree was granted on 12 November 1883. She married again two years later and lived happily in Sussex, but her marriage settlement from her first marriage was still active. Dumbreck, who remarried in 1896, was still reaping the benefits of her fortune. Although she petitioned the High Court for a change, she was un-successful and Minnie would continue to pay the costs out of her own settlement to the man who treated her brutally for just under a decade of her life.

Jacintha Hesketh (Major Thomas Hesketh’s widow and mother of six) married Thomas Winckley in 1785. They had one daughter, Frances, born 1787. After they had married everything Jacintha possessed became the property of Thomas Winckley. The Winckley family name ended with Thomas Winckley, who died in 1794. When he died he left his wife only one house and the rest of his vast estate went to Frances. He also left over £2000 inheritance to his two illegitimate sons whom he had fathered before his marriage to Jacintha. Jacintha’s five daughters, according to Frances Winckley’s diary, were greatly disliked by him and lived separately from Frances. Her diary records that her mother’s home ‘was not a happy one’. Jacintha’s daughters, whom we would see as the rightful inheritors of the Hesketh/Winckley estate, were left with nothing when Winckley died. When Frances married John Shelley in 1807 (63 years before the passing of the Married Women’s Property Act 1870) any money made by a woman either through a wage, from investment, by gift, or through inheritance automatically became the property of her husband. On Frances’s marriage all of the Winckley estate became the property of the Shelley family. One property was sold to pay his gambling debts! The Married Women’s Property Act of 1870 was too late for Jacintha Winckley and her daughters.

Jacintha Hesketh.

Other women were forced to adapt – take Elizabeth Swain for example. After her first husband died in June 1812, she went into trade with another woman Margaret Higham, as straw hat manufacturers; they were very successful and highly regarded. Almost twenty years later, immediately after her second marriage to John Swain in 1831, Elizabeth retired and moved into 29 Winckley Square. For most of their marriage John Swain did not live with his wife. When he died in the early 1850s he left her only £5 in his will and actually left several houses in Preston to his mistress. During this time Elizabeth was acquiring her own private income, though modest, from renting out her old bonnet shop and the house next door to her on Winckley Square. This meant by the time of her death she was able to live self-sufficiently. Elizabeth went to a great deal of trouble to make sure that her female relatives were not only left with a fair share of her estate in her will, but also, it was theirs and theirs alone. She did not want their share of her estate to be affected by the law that stated that when a woman was married her property then belonged to her husband – a law criticised and lobbied against by Caroline Norton.